More actions

The 1st Battalion of the Border Regiment seemed to be in limbo, at least for a while. The Division to which it belonged was supposed to have been mobilized on the 18 January but this did not materialise for a further two months when the Battalion, now at a strength of 810 other ranks and 26 officers, was reviewed along with the Division by the King. The 29th Division was at this time commanded by Major-General A.G. Hunter-Weston, C.B., DSO, having replaced Major-General F.C. Shaw who was badly injured on active duty in France. It was clear that "the Division represented about as fine a body of men as had ever been collected together, but possessed the one disadvantage that there had been little or no opportunity for combined training."[1] It was important that the Division worked uniformly and having no combined training was a problem but nothing that the Division couldn’t handle; it was inevitable that there were going to be many deaths as a cause of front-line fighting. It was around this time that the order to wear identity discs was issued and before the men were to set sail to their, as yet unknown destination, all ranks had to undergo anti-typhoid inoculations.

It was shortly after the Royal inspection of the Division that it was able to prepare for embarkation. Even though the men did not know for sure of their final destination, the general feeling was that it was the Dardanelles; an unexplored theatre of war. To understand why, at this juncture, this Expeditionary Force was detailed to fight at Gallipoli, a little explanation is needed.

Why Gallipoli?

One of the main factors of sending the Force to the Dardanelles came about when Turkey decided to join the Central Powers of Germany and Austria-Hungary (see here for How the First World War started with information on the Central Powers and Allied Forces). This monumental decision changed things dramatically and was the result of the loss of many lives on both sides. Britain had been in support of Turkey maintaining control of the Dardanelles and was keen to retain this preference over Russia simply because Britain did not want Russian war ships controlling what was essentially an important trade route between her shores and that of India. The British Government had to make a decision about what to do, and the serious considerations to gain control over this essential passage was something not taken lightly. Britain firmly believed that a successful operation here would bring an end to the Ottoman resistance and open up access from the Mediterranean to the Black Sea.

The initial attacks, in early November 1914, came not from land forces but from long-range naval bombardments. These only had minor effects and did not yield any purposeful results as to make any difference. This came to a halt almost as quickly as it had started and with this break in activity, the Turkish and German allies spent the next three and half months rebuilding and making further advancements in their fortifications along the strait. Essentially, Britain had given them enough time for an effective repeat strike against them with worthy gains almost unattainable. The naval bombardments began again in February, 1915, but again to little avail mainly because in the time spent fortifying the strait, the number of mines were now so acute that it was virtually impossible to get any ships through without causing major damage to the fleet. It was March by this time and there still had been no effective attack made thus far. It was on the 12 March that Field-Marshall Lord Kitchener informed General Sir Ian Hamilton that he was to have command of the military force that was to attack at the Dardanelles adding that "I hope you will not have to land at all; if you do have to land, why then the powerful fleet at your back will be the prime factor in your choice of time and place." General Hamilton had a difficult task ahead of him; forcing this passage to victory did not yet appear to be unreachable but in time, he and those of the cabinet back home, would soon come to realise how wrong they were that a wholly successful conclusion could not be reached here. Gallipoli would turn out to be something different than they had anticipated.

Embarkation

The 29th Division was one of several divisions that made up the Expeditionary Force that was to land on Turkish soil. Also part of the Force was the 42nd East Lancashire Division, The Royal Naval Division, an Australian Division, another Division of Australians combined with New Zealanders, two French Divisions and Indian troops. These numbered no more than 100,000 men of all ranks but it seems that this figure was not substantial enough for the task ahead of them. Further to this there were problems with the embarkation in as much as "those responsible for shipping the troops did not know what the army was intended to do, what was the plan of operation, and as a result units were packed anyhow on the ships – gunners without their guns and ammunition, engineers without their stores, and infantry separated from their transport – so that the whole expedition required to be organized and sorted out before the idea landing on a hostile shore could be in any way considered."[2] This was disastrous and added to the inefficiency of what was supposed to be an organised and superior Allied fighting force. There is no doubting the ordinary men but it is difficult to believe that if the Force’s commander was not out of the country at the time, he would have seen what was happening upon embarkation, acted upon the accordingly and set things straight, knowing full well that for a successful attack on hostile shores the Force needed to be fully prepared and ready for battle. This simply was not the case.

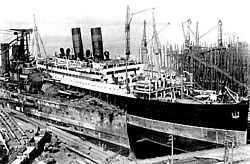

The 1st Border Regiment embarked at 5.30pm on the 17 March from Avonmouth on board two ships; the RMS Andania accommodating 887 men and 26 officers and the HMS Duke of Edinburgh accommodating 1 officer and 115 men. To see a table of officers who embarked with the Battalion, click here. They reached Malta a week later on the 24 March, remained there for two days before embarking again on the 26th, leaving 9 men in hospital there. The Battalion arrived in Alexandria on the 28th but did not leave the ships until the 30th when they marched 4 miles to Mex where they camped, taking part in field exercises and boat landing practise. They marched back to Alexandria on the 8th April embarking again on the same ships previously with the inclusion of a few men and transport animals on the Mercian. On the 10th they set sail again landing at Mudros Bay[3] on the 12th, a journey taking them past Tunisia, Sicilly and mainland Greece. For 10 days the Battalion remained here. The time was spent drawing up plans for a successful landing on hostile shores; men trained in rowing and landing boats and climbing up and down rope ladders, something they were expected to do upon the rocky outcrops of much of the coastline at their destination.

The Landing

The waters and land in which they had to traverse was filled with dangers. The fortifications on the Gallipoli peninsula were protected and well armed. The cliffs rise out of the sea to considerable heights and at "rare and irregular intervals these cliffs are broken by the ravines and gullies down which the winter rain escapes, and at the mouths of these gullies are generally strips of stony or sandy beaches. Inland the ground is much broken and roughly indented with gullies, clefts and irregular valleys."[4] Not only were the men facing a strong opposing force they were also facing another enemy, the land that they would find just as difficult. It was clear that this place was going to test them to their abilities and they would be thankful for the training they received prior to landing as without it their task would have been insurmountable in comparison. They did have one advantage and that was the irregular valleys, using them as communication avenues, the most important being Gully Ravine, Krithia Nullah[5] and the Kerves Dere.

The operation which the Battalion and that of the entire Force was involved was named after Cape Helles. Not far from Helles was the village of Krithia and the hill of Achi Baba[6], naturally strong defences that needed to be taken during the landing. The 29th Division were to land at Helles at five different beach locations named S, V, W, X and Y. The troops were all but ready and awaited orders for the advance onto the beaches where they could effectively start a land attack towards Krithia, the only feasible option for a successful claim on Achi Baba.

The Divisional Commander’s speech to his troops before the attack is as follows:

- “The Major-General Commanding congratulates the Division on being selected for an enterprise the success of which will have a decisive effect on the war. The eyes of the world are upon us and your deeds will live in history. To us now is given an opportunity of avenging our friends and relatives who have fallen in France and Flanders. Our comrades there willingly gave their lives in thousands and tens of thousands for our King and Country, and by their glorious courage and dogged tenacity they defeated the invaders and broke the German offensive. We also must be prepared to suffer hardships, privations, thirst and heavy losses, by bullets, by shells, by mines, by drowning. But if each man feels, as is true, that on him individually, however small or however great his task, rests the success or failure of the expedition, and therefore the honour of the Empire and welfare of his folk at home, we are certain to win through to a glorious victory.”

The 1st Border Regiment, along with the Royal Irish Fusiliers, had the task of landing on X Beach. Whilst this stretch of beach was considered not as difficult as other areas along the landing zones it was well covered from the Asian side of the strait. The beach itself was about 200 yards long, which was at the base of a steep slope about 50 or so feet high; this shouldn’t have posed too much of a problem if they weren’t exposed to lethal fire from the enemy at Krithia. It was on the 25 April that the fleet arrived just off the coast at Cape Helles. They remained at a distance of about 3 miles while the final preparations were made for the landing parties. It was very early morning and by first light the Navy began their fearsome bombardment on the peninsula. During this time the covering parties, in this case the 86th Infantry Brigade, made their way to X Beach where they landed without too much hostility but by the time they reached the open area overlooking the beach bitter fighting ensued.

At 7.15am, over two hours since the bombardment began, the men from the 1st Battalion had their turn to disembark the comfort of the Andania along with their comrades the Royal Irish Fusiliers. The 1st Battalion were minus the men from the Duke of Edinburgh transport ship but were still at a total strength of 950 all ranks. Once on the beach the men were formed into companies and awaited orders, which eventually came through at midday. ‘B’ Company had to support the attack being made on Hill 115 as the Royal Fusiliers were suffering terribly. There was blind fire in all directions over the top of the cliff and this made it impossible for the advance to continue without too much loss of life. There was no way that the 1st Battalion could join up with those who landed on W Beach as originally planned. The Royal Fusiliers had to fall back and ‘C’ and ‘D’ Companies of the Borders, led by Captain Harrison, were given fresh orders to make at once, a charge on the enemy who were only some 400 yards away. This they did under extremely heavy fire with a certain degree of success following the retreat of the enemy for 600 yards to the east. At the same time ‘A’ Company was involved in helping the situation on a ridge to the north-east. Their advance was steady and well organised, progressing some 1000 yards without too many losses to their numbers. Orders were given for the men to dig in at their current locations and the Battalion, at this point, around 3pm, held their lines. By the end of the landing, ‘B’ Company had suffered heavy losses supporting the attack made on Hill 115; the casualty list for this day is as follows: killed - 2 officers and 25 NCOs and other ranks; wounded - 3 officers and 78 other ranks.

By the end of the day, Sunday the 25 April 1915, reports were coming through as to the situation of events that had taken place. The V Beach landing failed, all further attempts to land there were abandoned with the forces being diverted to W Beach. The positions held at W Beach were holding although the safety of the entrenched troops on the higher ground was uncertain at that point. X Beach had been secured and at Y Beach there was a desperate attempt to hold the very sand they were standing on due to fierce continual attacks by growing numbers of the enemy. The fighting remained constant till dawn after which the Turks fell back, having lost heavily in numbers themselves.

The new day brought about surprisingly little action. The Battalion were aware of the snipers that had skilfully concealed themselves amongst the trees, some men already becoming casualties as a result of random fire. They passed the time as best they could, as they did on the 27th up until midday whilst things were still relatively quiet. Later in the day the infantry attacking another hill, Hill 138, were almost at the point of taking it along with the Old Castle. Our guns continued to open fire and the eventual capture of these came through as the Turks fell back to their lines at Achi Baba. Progress had been made and the sniping came to an end. The tension on the front line was eased for the time being.

Fresh order were received and the Battalion’s new objective was to ascertain a new line due east from the right of ‘A’ Company’s present position. The men had to dig new trenches and during the heat of the day this was made difficult from lack of energy and most likely thirst. By midnight the line was, however, complete. The men rested for the remainder of night in relative peace and quiet. By the morning the Battalion had been issued with new orders from Brigade HQ. Their latest objective was a new line, however, this did not mean digging new trenches, this meant a whole new advance was to be made. After the previous day’s events of digging new trenches through uncomfortable heat, the men probably did not welcome the task ahead of them, some not having been able to rest properly during the night. As the men of the Battalion advanced, shell fire on their trenches hit with incredible accuracy but this did not stop the attack. The Battalion, along with the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers found their feet and continued in line of platoons of at 100 yard intervals. Gully Ravine was crossed without too much resistance and they continued their advance. The next crucial point would be that of the village of Krithia.

Attack on Krithia

As with the 1st Battalion of the Border Regiment, the Royal Inniskilling Fusiliers were advancing to their objectives, which seemed incredibly distant taking in the entire length of Gully Ravine. Both battalions were the first to arrive at the southern area of the Ravine where it joins Gully Beach. They secured the area at this point with little to no resistance[7]. The advance continued with the "Borders advancing along the bare strip of rocky ground that became known as Gully Spur, and the Inniskillings on the eastern side of the ravine along what became known as Fir Tree Spur…by midday the advance had lost momentum; it was hopelessly disorganised and beginning to incur casualties. A Turkish strongpoint, near the abandoned Y Beach, put up heavy resistance that brought the advances to a standstill. These tired invaders were not in a fit state to carry out an attack."[8]. The R.I.F. encountered very heavy machine gun and rifle fire and at this point it became apparent that the 1st Battalion Border Regiment had to advance at least another mile or so if it was to be of any practical use to the situation. Fierce counter attacks had broken their advance. Naval support helped the weary 1st Battalion and "as the smoke and dust cleared, the Borders rallied and re-established the line." [9].

They pushed on, two platoons from ‘A’ Company eventually finding the former trenches of the King’s Own Scottish Borderers and two platoons from ‘B’ Company progressing a further 300 yards, forming a firing line across the ridge. ‘A’ Company came under heavy fire from the North West ridge of Krithia but owing to the nature of the topography they were unable to retaliate. After ‘B’ Company were suitably secure, ‘A’ Company followed suit. In the distance the enemy could be seen retiring to safety behind the North West ridge, which from the observer was a sign that their efforts were taking on great effect, but this was not exactly so. Almost at the same time the Battalion came under further heavy machine gun and rifle fire from trenches so well concealed on the other side of the valley that they were not detected. Men were dropping all too quickly and the damage was high. The call for reinforcements was made but they could not reach them as they too were involved in the bitter fighting, effectively holding them up. A delay in reinforcements meant further casualties by both front line and support. The higher ground by Krithia was the perfect vantage point for the enemy and this caused heavy loses amongst the support and reserves. What originally looked like another step closer to a victory at Krithia and another step closer to Achi Baba, turned out to be something very different indeed.

The 29th Division had taken a beating over the previous couple of days fighting but were still holding fast. Casualties were high, water was becoming scarce and the food[10] they were issued with for the initial 25 April Landings now had to be eked out for another day, a meagre intake under such harsh, energy reducing conditions.

It took a little time before the bulk of the reserves could make their way forward by use of a small nullah. The call for reinforcements was responded to with great effect, even with the men waning as a result of the steep climb, the heat and the weight of their packs. Yet with reserve numbers adding to the Battalion’s front lines, the enemy outgunned them at frightening odds. The officers of the Battalion suffered many casualties as the enemy moved in closer under covering fire but "Captains Morton and Moore, by their fine example of coolness and courage, had kept the firing line steady, but now the cry to ‘retire’ was raised on the right and a somewhat precipitate retreat set in, and it was with some difficulty, and chiefly through the gallant exertions of Colonel Hume, Captain Morton and other officers, that the line was rallied and a fresh defensive position taken up 200 yards S. of the K.O.S.B. trenches."[11] As a result of their actions the line was held and later, with support from the Royal Naval Division and South Wales Borderers, the tense situation was restored, however, Colonel Hume was shot soon after and subsequently died of his wounds on the 1 May, a great loss to many.

The remaining men of the Battalion were ordered to move back and assist the line that was currently being held by the Brigade. The fighting had at this time started to decrease and their withdrawal was met without loss simply due to Captain Morton’s decision to retire to the Brigade’s position after night had fallen instead of when he was actually order to. The cover of darkness, in his foresight, was the key to moving his men back without a single casualty. The casualties for the day were thus: killed - 4 officers and 25 other ranks; wounded - 5 officers and 131 NCOs and other ranks[12]

There was relative quiet on the night of the 28th and early hours of the 29th. The Royal Naval Division was, however, withdrawn during the 29th and the 1st Battalion, now holding their position alone, took a large amount of shelling. Their numbers were added to when 88 men and 2nd Lieutenant Cay joined them from X Beach. They were supposed to have assisted the Battalion on the front line the day before but were unable to due to the unsuccessful attempt of finding their unit during all the chaos. With this additional support the line was better fuelled for a further day before all ranks of the Battalion were order to Y Beach as Brigade Reserve. It was here that they remained for two days in comparative safety and quiet away from the first hand conflicts that sporadically took place on the front line.

Before the men of Battalion had sufficient time to recoup they were issued with fresh orders to make their way forward via what they called the Sniper’s Hut, to take position in the first of the firing lines they met with. The advance towards Achi Baba was still a prime objective and so they set off heading in that direction as ordered. The fire from both sides during the evening of the 2 May through to the morning of the 3rd was intense and it seemed that the Turks were desperately attempting to push forward and break the much thinner British line. By daybreak the Battalion had moved to a position between the South Wales Borderers on the left and Royal Fusiliers on the right in preparation for a counter-attack. At the time given the men rushed forward, led by Captain Morton, and made their way to the firing trenches under considerably heavy fire. The trenches were already overcrowded and getting there was difficult but not impossible. When there was a slight break in the firing, Captain Morton took his men and charged towards the enemy trenches where it seemed that they could, with any luck, take their objective. At such a close range it was almost within reaching distance when suddenly Captain Morton and Lieutenant Perry were killed and Captain Ellis, who was also Adjutant, was wounded bringing up the reserves. Only 10 yards or so away from the enemy trench a dozen men were the only ones left who managed to get this far in the initial charge. They managed to dash into a shallow trench and stay there until they could retreat one at a time to safety. This they managed about half an hour later without further loss. When they rejoined the rest of Battalion, it was ordered back to Gully Beach.

Over the next few days the Battalion was involved in further advances on the enemy line, gaining more ground each time but at a cost. Part of this advance took place at Fir Tree Spur[13], where the 5th Royal Scots had been engaged in bitter fighting since thier initial attack on the woods at 10am. It turned out that what they found was a "wood full of snipers, body and rifle painted green, camouflaged with twigs and brances from the trees, so much that they resembled trees and bushes."[14]. They suffered with heavy casualties. The 1st Battalion Border Regiment, 1st Essex Regiment and Dubsters[15] attacked at 5pm, advancing into the woods as far as 300 yards before they were driven out by determined and successful counter attacks by the Turks. Further heavy casualties were the result of the day's attacks. By the 8 May though, the Battalion was ordered back to X Beach to form part of Divisional Reserve and it was here that the men spent the following three weeks away from the front, making the most of the less hostile surroundings. The Battalion had a further two drafts of 40 and 90 other ranks respectively and three officers who were either injured in the initial landings or soon after also rejoined, these being Captains Nelson, Le Messurier and Harrison. The following officers joined the Battalion from England:

| Captain J.G.P Mostyn (Norfolk Regiment) | Captain H. Millard (Northamptonshire Regiment) |

| Second-Lieutenant Wallace | Second-Lieutenant N. Castle |

| Second-Lieutenant H.R. Wright | Second-Lieutenant T.L. Wilson |

| Second-Lieutenant R.F. Millard | Second-Lieutenant P. New |

| Second-Lieutenant J.L.E.R. Lake | Second-Lieutenant W. de H. Robinson |

| Second-Lieutenant F.B. Goodall | Second-Lieutenant P. de Soissons |

| Second-Lieutenant B. Bradshaw |

By the 4 June the Battalion was no longer in Divisional Reserve. Gully Ravine had become a familiar place, unliked by most, if not all, men who were resident here on a regular basis. Sergeant S. Evans of the 1st Battalion provided a detailed account of what this area was like around this time, nicknamed "The Valley of Death." By the 10th, after there had been an increase in enemy activity, the Battalion was engaged in putting together a party for the successful capture of the enemy’s sap and communication trench located further up the ravine. As was the case with many of these types of operations, volunteers were called for. It did not take long before there were around 30 men willing to take part. Led by Second-Lieutenant Wallace, they made their way to the enemy’s sap by way of crawling over the parapet and charging despite the heavy fire. Upon reaching their objective they bombed and bayoneted the enemy and took control of the trench system some 200 yards in length. After having seized the trench, ‘D’ Company held it during the night under the command of Captain Le Messurier. Captain Harrison had again been wounded for the second time. The very next day a message was received by General Hunter-Weston stating that "the G.O.C. Division congratulates all ranks on the excellent work performed by them last night, and feels confident that they will hold the ground gained at all costs." Along with this congratulatory message also came a draft of 228 other ranks and 4 officers from England.

The communication trench captured was on the night of the 11th and early morning of the 12 June counter-attacked after a small bombardment that took place at 1am and 3.30am respectively. For a short while the men lost their position to the enemy but regained it when Captain Moore charged and took it back. In the process he was killed from a bullet to the head; Captain Le Messurier was wounded as were Second-Lieutenants de Soisssons and Bradshaw. After this brief encounter at arms the Battalion was again sent back to Gully Beach where the men spent another week away from the danger of the front. By the 17th, they were back in the thick of it having to cope with very heavy shell fire. Then, Battalion HQ was destroyed by a shell killing three men and wounding four others. Over the next few days they were back at Gully Beach and supplied with more officers, who as a result of the recent fighting, needed replacing.

Taking the Boomerang Redoubt

The process of front line action and taking up reserve positions on the beach was a frequent occurrence. They had spent as much time on the front as they had in reserve, which was important for the Battalion as men cannot function properly as a fighting unit if they are fatigued. They may have been out of immediate danger but this does not mean they were safe; this was always relative regardless of location. Sometimes it is not always possible to rotate the Battalions from front line to reserve or billets quickly enough because of specific circumstances dictated by what is happening at the time but at Gallipoli, at least with the 1st Battalion Border Regiment, it is clear that there was a working system of one battalion relieving another.

The 1st Battalion had since been back to reserve and again back to the front line when on the 27 June were issued with new orders to attack the enemy positions at the Boomerang Redoubt, and that of Turkey Trench, also held in enemy hands. Sergeant Evans describes going into the line on the afternoon of the 27th: "At 4.30pm we dress in full marching order and set off up the Gully once again. The day is intensely hot, the hottest we have experienced so far and before we have gone far the perspiration is running off us like water. The heat and dust, together with the heavy weight of our equipment is trying to the most seasoned veterans and we are glad when we get a halt half way up."[16]

The 1st Battalion's task was an important one as this area, unsuccessfully taken after three attempts, was needed to straighten out the line. The day before saw them in preparation for their attack, which was going to take place on the 28th. "The Borders were to move up the ravine in order to rush the Boomerang redoubt and the small portion of Turkey Trench still held by the Turks. This was the most advanced part of the Turkish line, heavily fortified with a triple depth of wire, behind which lay machine guns, holding this vital strategic point from which Turkish fire could sweep all the surrounding area, especially that on Gully Spur."[17] ‘B’ Company under the command of Captain Forbes-Robertson were to take the Boomerang Redoubt whilst Captain Mostyn commanding ‘A’ Company were to take the enemy trench. At 9am on the 28th, another hot and uncomfortable day, the British bombarded the Boomerang and enemy lines with deadly accuracy and when the time was called, both companies advanced towards their objectives as quickly as they could under the cover of dust that had been thrown up by the constant shelling over the previous two hours. The barrage was lifted off the Boomerang at 10.45am exactly, the Borders having already readied themselves with bayonets fixed. Sergeant Evans recalls the moment just before attack commenced: "One further minute and the word 'Ready' is passed along. In that one minute we unconsciously take one look at the sun and the sea and involuntarily commend our bodies and souls to our Maker - and then before we realise it a hoarse shout of 'Over' and we are up the ladders and racing like the wind for the redoubt and 200 yards distant."[18]

The redoubt was reached relatively quickly and without hostile fire owing to the lack of general visibility. The men from ‘B’ Company went forth and charged the redoubt with a combination of bombing followed by bayoneting and were soon met with their support, which suffered a few casualties in transit. ‘A’ Company did not fare well in the attack and were all but wiped out due to hostile fire from an adjoining trench to their objective. Even their support suffered greatly but reinforcements were gathered and under the command Sergeant Wood managed to break through and eventually join up with ‘B’ Company in the redoubt. As a result of the bitter fighting that took place, 64 Turks surrendered and were taken prisoner, many others were killed. The fighting here in the 'Battle of Gully Ravine' continued with other battalions from all Brigades in the 29th Division (see here for Order of Battle) advancing on their objectives. The 1st Battalion, however, had succeeded in capturing the Boomerang and Turkey Trench system and is immortalised in a poem about this victory. Even though the whole operation was thoroughly organised and well planned, not to mention a success, they couldn’t have anticipated the enemy activity from the adjoining trench and so the loss of life from the assaulting party on Turkey Trench was great indeed. General Hamilton later described the attack by the 1st Battalion Border Regiment thus:

- “At 10.45 a small Turkish advanced work in the Saghir Dere known as the Boomerang Redoubt was assaulted. The little fort, which was very strongly sited and protected by extra strong wire entanglements, has long been a source of trouble. After special bombardment by trench mortars, and while bombardment of surrounding trenches was at its height, part of The Border Regiment at the exact moment prescribed leapt from their trenches as one man, like a pack of hounds, and, pouring out of cover, raced across and took the worst most brilliantly.”

Further to the success at the redoubt the process of further fortifying their positions, particularly in Gully Ravine, saw the construction of the Border Barricade, which marked the furthest held point along the Allied line. The barricade was thus named after the Battalion who established it, the 1st Border Regiment. Attacks were made by the Turks to charge the ravine but to no avail. Every attempt they made only lessened their numbers as machine gun and rifle fire cut them down, not only once but several other times during failed attempts through the night. Their losses were heavy and by morning the aftermath of these attacks became apparent to the Battalion by the number of bodies that scattered the landscape before them. The losses of the Battalion were: killed - Captain Hodgson (by bayonet) and Lieutenant Dyer; wounded - Captains Harrison (3rd time) and May; Lieutenants Cay, Rupp (2nd time) and Adair; Second-Lieutenant Millard. The number of killed, wounded and missing other ranks totalled 153.

The following Special Force Order was published by General Sir Ian Hamilton regarding the success of the operations of the 29th Division that day states:

- “The General Commanding feels that he voices the sentiments of every soldier serving with this Army when he congratulates the incomparable 29th Division upon yesterday’s splendid attack, carried out, as it was, in a manner more than upholding the best traditions of the distinguished regiment of which it is composed. The 29th Division suffered cruel losses at the first landing. Since then they have never been made up to strength, and they have remained under fire every hour of the night and day for two months on end. Opposed to them were fresh troops holding line upon line of entrenchments flanked by redoubts and machine guns.”

- “But when yesterday, the 29th Division was called upon to advance, they dashed forward as eagerly as if this were their baptism of fire. Through the entanglements they swept northwards, clearing our left of the enemy for a full thousand yards. Heavily counter-attacked at night, they killed or captured every Turk who had penetrated their incomplete defences, and to-day stand possessed of every yard they had so hardly gained. Therefore, it is that Sir Ian Hamilton is confident he carries with him all ranks of his force when he congratulates General Hunter-Weston and de Lisle, the Staff, and each officer, non-commissioned officer and man in the Division, whose sustained efforts have added a fresh lustre to British arms all the world over.”

The 1st Battalion returned to Gully Beach on the 7 July where it marched to V Beach on the evening of the 11th. They were to have a well-deserved rest after the fighting they had been involved in since landing on the 25 April. They returned to Mudros, two companies and the Battalion HQ taking temporary accommodation aboard the HMS Renard and the other two companies in trawlers, where they stayed for a further 10 days to recoup. Rejoining the Battalion after recovering from injuries were Captain May and Lieutenants Wilson and Lake. Along with a draft of 199 other ranks were Major F.G.G. Morris, Second-Lieutenants Ampt, Chambers and O’Brien. It was here that Major Morris took command of the Battalion.

The 1st Battalion’s next journey takes them to Suvla further along the Gallipoli coastline, which marks the continuation of their history in the Suvla Operations of 1915.

Map of Cape Helles War Zone, 1915

This map clearly shows the locations of the Landing Beaches S, V, W, X and Y as well as Gully Beach, which leads to Gully Ravine and the Boomerang Redoubt. The village of Krithia, the nullah that leads to it and the Turkish strong hold of Achi Baba, located at the top right of the image, shows the route and gives a good idea about distance that the 1st Battalion, along with others from the M.E.F., had to take.

Footnotes

- ↑ Wylly 1925, p.40.

- ↑ Wylly 1925, p.41-42.

- ↑ Mudros Bay being situated on Lemnos, an island in the north Aegean Sea and only 50km from the Dardanelles Strait.

- ↑ Wylly 1925, p.43.

- ↑ A nullah, sometimes steep and narrow valley usually characteristic in hilly or mountainous landscapes.

- ↑ Achi Baba, rises approx. 700 feet, commands all of the land in which it stands was. It is a prominent point on the Gallipoli peninsula landscape.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.24-25.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.25.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.26.

- ↑ Two days rations for the 25th and 26th of April and one iron ration for the 27th. An iron ration consisted of bully beef, two 'hard-tack' biscuits, some tea and sugar.

- ↑ 1st Battalion War Diary, April 1915

- ↑ This is subject to discussion as the war diary, having two slightly varying copies, shows a different set of figures; from this it is diffucult to say which one accurate.

- ↑ Later known as the Battle of Fir Tree Wood.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.33.

- ↑ This was a composite battalion made up from the Dublin Fusiliers and the Royal Munster Fusiliers.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.78. Original Source: My Gallipoli Story by Sgt S. Evans, The Gallipolian, No.45, Autumn 1984, p.28.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.77.

- ↑ Chambers 2002, p.78. Original Source: My Gallipoli Story by Sgt S. Evans, The Gallipolian, No.46, Christmas 1984, p.20.

References

Books

- H.C. Wylly, C.B. (1925). The Border Regiment in the Great War. Gale & Polden Ltd. ISBN 1843425408

- Stephen Chambers (2002). Gallipoli: Gully Ravine (Battleground Europe). Pen and Sword Ltd. ISBN: 0850529239

Military Records